Islip historical society to publish Civil War soldier's donated letters

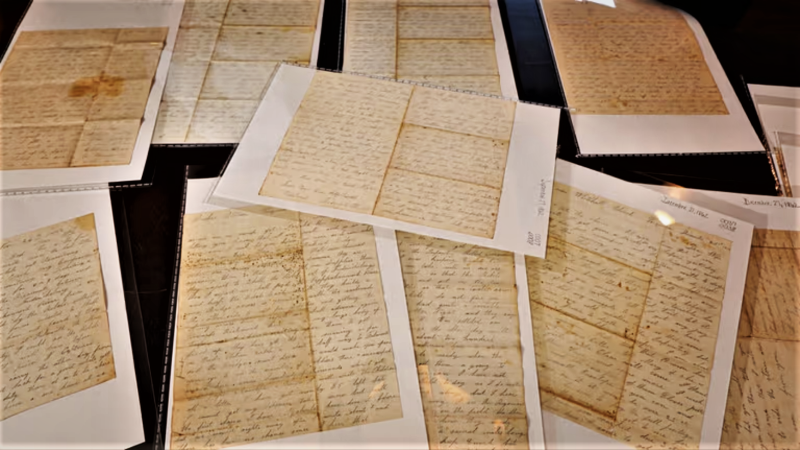

Robert Finnegan, from left, Madeline Hanewinckel and Victoria Berger, all members of the Historical Society of Islip Hamlet, look over a sampling of the 97 letters written by Islip resident and Union Army soldier Frederick Wright Sr. that he wrote to his wife while fighting in the Civil War. Credit: Newsday/John Paraskevas

A Civil War soldier’s 160-year-old letters, discovered in a shoe box in Rhode Island, have been donated to an Islip historical society where they are being transcribed and made into a book.

The letters were written by Frederick Wright Sr. to his wife, Phoebe, during his service in the Civil War from 1862 to 1865. The Islip man, who worked as a wheelwright repairing wooden wheels, joined the Union Army at 41, alongside sons Frederick Jr. and Lee. The 97 letters, which historians have called a unique find, offer a glimpse into Wright’s daily life during his service with the 2nd New York Cavalry.

The letters were donated to the Historical Society of Islip Hamlet by Paul Perryman, of Riverside, Rhode Island. Perryman’s mother, Marcia, had kept the letters belonging to her great-grandfather until her death in 2008. When combing through his mother’s possessions, Perryman discovered the family heirlooms. He said he didn’t want them “to stay hidden in a shoe box” as they had for decades, so he donated the set to the historical society in 2019.

Some of the 97 letters written by Frederick Wright Sr., an Islip resident and soldier in the Union Army, to his wife, Phoebe, during his service in the Civil War from 1862 to 1865. Credit: Newsday/John Paraskevas

Wright was one of the 121 men from Islip who joined the Union Army, said Rob Finnegan, a founder of the historical society who is transcribing the letters. He plans to publish a book in the next year featuring copies of the original letters next to his transcriptions. Finnegan said the letters don’t express feelings about slavery or politics and he suspects Wright might have joined the Union Army for the economic incentive, which wasn’t unusual.

“These letters are very interesting,” Finnegan said. “They’re well written, although there’s little punctuation [errors] and some typos, but they’re done very, very well.”

The letters offer insight into Wright’s feelings about the war’s progression, Finnegan said. Wright mused in three letters that he thought the war would end before he completed his training. After the Fredericksburg battle in 1862 — one of the largest and deadliest of the war — Wright wrote a disheartened letter home expressing concern that the Union Army could fall to Confederate troops. He called the battle “a slaughterhouse” and “a terrible loss of life,” adding that some men froze to death.

His letters were restrained, Finnegan said, likely because Wright knew his wife shared the letters with their children. During the war, he held a smattering of jobs, such as a hospital cook, a physician’s orderly and a supply train guard, and also went on raids. Wright wrote that he preferred being an orderly — eventually outgrowing his squeamishness around blood and limb amputations — to embarking on raids.

Victoria Berger, executive director of the Suffolk County Historical Society, helped preserve the letters, which she also scanned and photographed to digitally enhance. The letters, written in pencil, are difficult to read. Some were written on thick, government-issued paper, but others were scribbled on paper as thin as tissue, she said.

“To have such a complete collection of letters from the same soldier, that’s the first that I’m aware of … locally,” Berger said.